Virginia Department of Education’s new cell phone policy is yet another blow to Virginia’s student journalists. In a state that does not guarantee press freedom for high school students unlike many of its counterparts, educational policy is being implemented without taking the unique consequences student journalists will face into consideration. Beginning January 1, 2025, many Virginia public school students will be required to go phone-free from the start to the end of the school day. The new “Cell Phone-Free Guidance” came in response to Governor Glenn Youngkin’s Executive Order that directed the VDOE to create a policy that removed all cell phone usage from the classroom. High school journalists across the state, who rely on their personal devices to record interviews, take photographs, and research information for their journalism classes, will undoubtedly be affected by the implementation of this plan. As journalism becomes a digitally centered profession, young Virginian journalists worry they will be left behind and unable to keep their peers informed.

Currently, phone policies differ by district. For all students interviewed, their district policies prohibit phone usage during instruction time while allowing them during passing periods and lunch shifts. Some districts allow students to have phones during class if permitted by teachers for instructional purposes. Many journalism program advisors have been flexible, allowing student journalists to have their phones when they are covering stories. However, VDOE’s new policy threatens to change these circumstances.

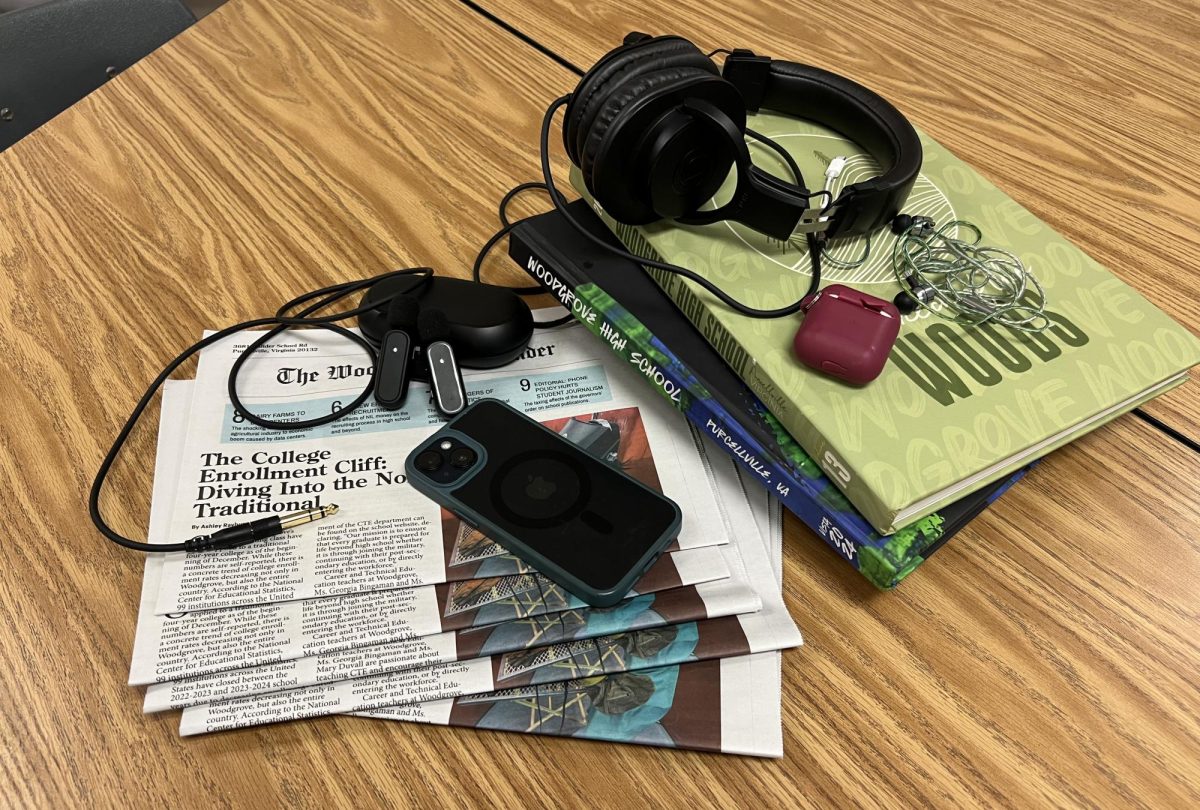

A cell phone allows journalists to keep an audio recorder, a camera, and internet access on their person whenever they are covering a story—all on a small device that fits in their pocket. A fact that remained constant with all student journalists interviewed is that they use their phones as audio recording devices. While district-provided Chromebooks are an option for audio recording, without additional equipment, the recording quality is not up to par with the recording quality of phones. Additionally, most cell phones have built-in audio recording apps that make it easy to quickly record and organize files. Sabry Tate, a managing editor for the newspaper of Lightridge High School in Loudoun County, commented, “I personally think the Chromebook audio is a lot worse than Apple audio or phone audio in general.” She believes that if Chromebooks are left as the only option, “that is going to lead to consequences that are negative.”

An alternative many classes are considering are separate handheld audio recorders. However, some student journalists take issue with this. Buying equipment like that can be expensive. Addie Harris is a senior at McLean High School in Fairfax County and a Managing Editor for the school’s student publication, The Highlander. She elaborated, “The school will spend a lot more money on our program than it currently has to, and you guys probably also know this—journalism is not really a cheap class.” With printing costs and fees for website platforms already costing a significant amount, the added expense of separate recording devices is an unnecessary burden for schools to bear, especially when many students already have a recorder in their pocket. It also raises the possibility for issues of inequity in journalism programs across schools in Virginia. Just last year, in a report called “Virginia’s K-12 Funding Formula,” the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission found that dozens of counties outside of Northern Virginia are not earning the money they should from the state for education due to a formula based on outdated local labor costs. As student journalists from Northern Virginia like us worry about the costs affecting their program, it is important to consider that this phone policy may have a disproportionate effect on school districts outside of the region who do not receive proper funding.

This same issue applies to another key use of phones in journalism classes: to take pictures. Cameras can cost thousands of dollars, and phones provide an alternative that many students have access to. When having to take quick camera shots on the go or snap an unexpected picture, phone cameras are the convenient solution. With phones no longer an option, journalism programs will be forced to either purchase new equipment or suffer the consequences. Harris of The Highlander explained, “We only really have three working cameras right now that are nice. And when we can’t have our phones out to document school events, it’s really hard to make sure those things are documented, and so it makes coverage a lot more difficult for us.” Student publications across the state should have the opportunity to provide meaningful coverage to their student body, and not having the money to spend on equipment should not be an obstacle to that.

Another significant use of phones in journalism is the use of social media to conduct research and promote student publications. Gone are the days when websites were constantly updated with things students need to know. These days, programs in athletics and the arts share all-district athlete lists, cast lists, and important dates via graphics on their Instagram accounts. Many school districts block social media on district-provided Chromebooks, so there is no way to access this information unless students use their phones. When asked about using phones to do research, Karan Singh, a junior and the Managing Editor for The County Chronicle, Loudoun County High School’s newspaper, explained, “We do that a lot. Especially me. Instagram—I use that for photo features a lot and to identify who is in a picture.” Singh also serves as the social media manager for his publication and has been left wondering what the future holds for that easy way of promoting stories. Without being able to research and promote publications using social media during the school day, VDOE’s new phone policy will leave much work to be done outside of class, which can discourage students from joining journalism programs and leave class time feeling useless. Harris explained, “When the state is limiting our resources even further by cutting down the amount of time we can use our phones, that’s really frustrating, because it requires us to put in more of our time. It makes our journalism classes less productive.”

With the imminent arrival of January 1 and the implementation of the “bell-to-bell” policy proposed by the VDOE, many students are left with a feeling of uncertainty for how their publications will get by without any access to cell phones. “As of right now, our teacher hasn’t really come up with a plan or anything. If I had to guess, I would say maybe we’re going to need to start just typing out what people are saying, even though that’s less convenient,” Abby Marquez said, referring to no longer being able to use phones to record interviews. She serves as the Editor-in-Chief of The Roar, the newsmagazine of Loudoun County’s Potomac Falls High School.

Even now, before the completely phone-free guidance goes into place, the current phone policy is impacting journalism programs. In McLean’s journalism department, which Harris joined in her sophomore year, the policy of no phones in the classroom is strictly adhered to and has been creating obstacles when trying to interview and contact sources. With the current restrictions, Harris and her classmates attempt to make use of valuable opportunities outside of class in order to get their work done. “Usually, we try and conduct our interviews during lunch or before and after school, because that’s when we are allowed to use our phone[s],” Harris noted. “So currently, students are just kind of trying to work around the phone ban.”

Although students worry about a future where they do not have access to their phones in journalism classes, they are not against phone policies being implemented in schools. Referring to the district policy of phones being banned in classrooms, The County Chronicle’s Singh stated, “The current phone policy, I actually like it. It is making me productive in school.” Marquez agreed, saying, “I think a lot of kids at first, when they heard about it, were like, ‘Oh, no, I don’t want to do that.’ You know, ‘My phone is my property. I’m going to keep it on me anyway,’ but so far, I think both kids and teachers have realized that the phone policy is pretty helpful. It helps us get our work done.”

A possible solution for this might be a special exception for journalism classes. Harris explained, “Although the phone policy has been really helpful in every other class, I think maybe they should look into certain exceptions for certain classes that relate to journalism or video editing, because in the future, you know, when we’re in college, or if any of us want to go into the creative field or video editing, in our jobs we’ll be able to use our phones. We’re not going to be limited to our desktop. So it would be nice if they made an exception for our class and would let us continue to do what we’re doing, because it’s not like the phones are a distraction…We are actually getting our video and article deadlines done.”

When creating policy that seeks to improve the productivity of public education, school districts and legislators should be careful to consider how it will affect student journalists and their ability to work during school hours. The complexities of smartphones demand that these policies are made while looking at every potential use of these devices in the classroom—from a holistic approach, not a divisive one. In the Department of Education’s process of catering to thousands of students, it is important that student journalists are not forgotten in these state-wide attempts to better schools. High school journalism brings to light stories that the adult world cannot fully reach, and for this reason, the voices of young journalists should be elevated, not restricted, within Virginia high schools.